Back to Cuba for Photos: Why Some Still Go

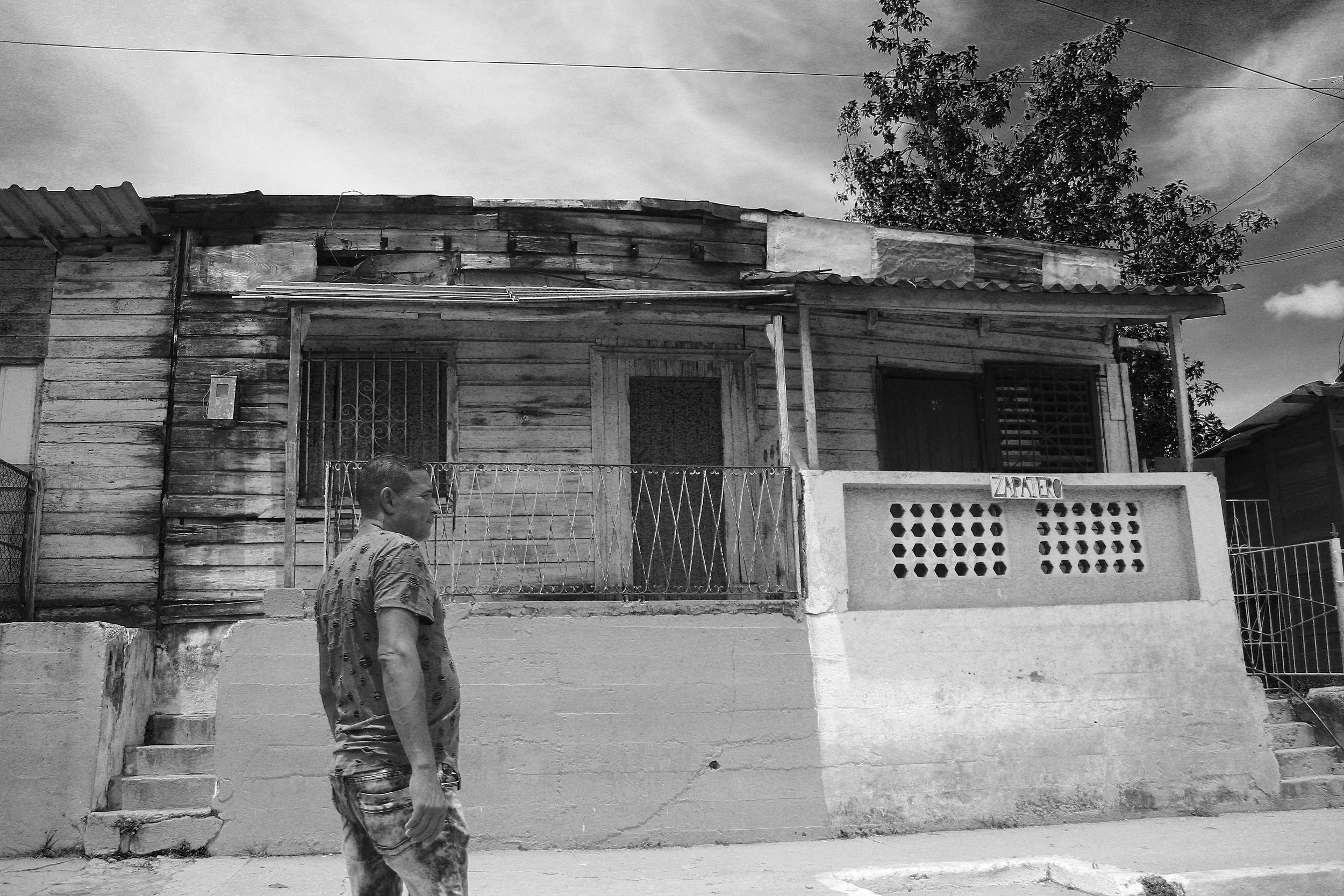

One of the things that has actively fascinated me since I left Cuba is seeing how many photographers continue to travel there. Over the past three years, I have seen my instagram feed pop up with excellent photos from very talented and/or well-known photographers of Havana, and not the Havana of the old (by old, I mean my last few years there), but a more recent and sadder Havana.

Photographing Cuba has been a thing since the age of the Great Depression. Walker Evans made a long trip and documented the worst that Cubans were living through the so-called Período de las Vacas Flacas (Age of the Thin Cows). The economic struggles, brilliantly portrayed in America by the great Dorothea Lange, were also hitting the rest of the world.

Even after my departure, Summit Workshops carried out one of its activities in the Cuban capital and other provinces. Photographers, unlike the common tourist, like to travel, explore and learn more from the common culture and the real struggles of the people there, That’s why many of the photos I find, although beautiful, evokes a sense of sadness and despair in me. I know what these people are going through, or, at least, I can relate. I was one of them once, and due to the many people I care about who still live there, I still am.

I had the misfortune of not discovering photography for real until 2010. And I had the bigger misfortune of never owning a really strong camera until 2014. My sample size as a Cuban photographer, although considerably large, is locked in only seven years that included working for a government-run and Communist-controlled newspaper for four of those, plus more than one and a half in full lockdown during Covid-19. Therefore, the best part of my photographic archives is centered between the last months of 2017 and the first months of 2020.

In a little over two years, my archive grew exponentially, mainly thanks to the work I was carrying out with I Love Cuba Photo Tours. However, that very work was slightly restricted to the areas of Central Havana, as the local authorities created a bush-league law that would lead to our arrests if we decided to perform our tours in Old Havana. My advantage was that I lived there, and that in my free time I was able to venture along the streets of what they called the Golden Strip and the really poor neighborhoods that surrounded it.

Why Cuba?

What really catches my eye is the fact that nearly every contemporary photography book that I find, that includes either teaching about photography or histories of photographers, will always include at least one photo of Cuba. Havana, Trinidad, Viñales, and other areas are featured in the color or black-and-white pages. Is it because Cuba is special? Maybe. Or maybe it is just because Cuba is a documentary photographers’ paradise, offering some of the best and most poignant images to be taken. In a twisted manner, Cuba welcomes them, embraces them, and gives them its all.

Even today, photographers continue to go. They haven’t been deterred by the worst wave of blackouts since the mid 1990s taking place, with the first largest immigration wave since the Crisis of the Rafters (also in the mid 1990s) and the Mariel Boat Lift, with one of the worst healthcare, social and political crises since Fidel Castro took over in 1959.

Cuba stands in its quasi dystopian reality, making those who ever read George Orwell wink and call him nothing short of a prophet. And as photographers, we cannot deny being captivated by the unique, bizarre, sad, angry. It has remained our duty to document the helplessness of some, so others can see how lucky they are or strike a cord on them to make them take action. Unfortunately, very little action is taken, and Cuba remains that little “paradise” that has been denied and neglected.

Sometimes, it feels like the world is so fascinated by the beauty of the documentary photographs taken by traveling photographers that they don’t want Cuba to change. Is it the old classic American cars? The post-apocalyptic look of some areas? The now vanished display of joy? The beauty and kindness of its people? A combination of all?

What people don’t know is that despite looking stalled in time, Cuba has kept on changing dramatically since the Soviet bloc collapsed in Eastern Europe.

Legalization of dollar holdings, creation of the CUC (Cuban Convertible Pesos or chavitos), opening to tourism, partially ending the demonization of christianity, allowing people to own cell phones and computers, opening up (slightly) to Internet and allowing a certain (yet, heavily monitored and persecuted) free and alternative media, opening up to Americans, allowing foreign travel. Feels like a lot of turmoil, right?

Yet, the one constant, at least until recently, was the rations card and the guaranty that every Cuban would have at the very least some necessities covered and subsidized. They would still have to struggle to get many essentials, and many of those would be completely out of their financial reach, but they could eat some.

Even that “perk”, the only one that came from having slave-like wages, is gone now. A desolated panorama engulfs the island nation, burying the roughly ten million people left there in sadness, despair, poverty and hopelessness. All those things, in the long run, make photos of Cuba even more worth documenting.

To Go or Not to Go?

The really tricky question, and where the moral compass might move erratically, is whether I would recommend photographers to go to Cuba or not. This question in itself poses a moral dilemma in both the economic and social aspects.

Economically, the million-dollar question remains in me actually suggesting that people go to Cuba and spend money there. Doing that, seeing with the black-and-white filter of politics, is unethical, because the vast majority of the money that comes to Cuba ends up in the private coffers of the rulers or help enhance the military-ruled domain of the communist dictators on the Cuban people.

However, we live in a grayscale world: bringing money and small resources to the hands of everyday Cubans will help them strive financially, become more independent of the government (hence more free-thinking individuals), or simply survive the many hardships that they encounter on a daily basis. At the same time, it will be in accordance with US laws, as part of the category known as Support for the Cuban People. This would include staying in private houses (as long as they don’t belong to anyone related to the Castro family or any other oligarchs), eat in private restaurants and taking private tours and workshops, most of which are better prepared, with more knowledge, and a free and truthful exposure to Cuba.

Socially, the conflict is not less complicated. For starters, coming to Cuba to photograph can be seen as a sort of voyeuristic and vulture-like activity. The country is suffering, and those who cannot make it out of there feel in some sort of captivity. So, taking photos of their suffering might be considered unethical and cruel by outsiders, and offensive by some people in Cuba who don’t want to be treated like they are in a zoo. Others will see it as a way to romanticize oppression, poverty and misery.

Yet, there are some caveats to that as well. Awareness is always going to be important to solve problems and to stand up to injustice. It will always be important to make people understand the sufferings and struggles of different social groups and communities. That is actually in a way the work that major publications like National Geographic do: going to less favored communities and documenting on their way of life. And how do you bring awareness? By showing people images that tell a story.

So, will I recommend any photographer to go to Cuba? The answer will always depend on other questions. Are you willing to stay in AirBnB places that are owned by people with no relation to the dictators whatsoever? Are you willing to stay away from government-run hotels? Are you willing to hire private tours and workshops that provide a truthful and honest window to Cuba’s underworld? Are you willing to put dollars (not exchanged money) in the hands of Cubanos de a pie (the Cuban way to refer to those people who can’t afford to have a car, which is the vast majority of the country)?

Then, my answer is yes. Book a workshop, whether it is based in Cuba or elsewhere, just make sure they have no links to the Castro family, to any of the ministries in the country (including the corrupt Ministry of Tourism); book your AirBnB (doing the same thing, as many fancy ones are run behind the scenes by relatives of the powerful).

After that, buy your plane ticket, fly to Cuba, don’t exchange more money than strictly necessary and put all that cash in the hands of people in need. Giving them some financial freedom will be a way to give them a little taste of what real freedom feels like. It also part of the game.

Below, a list of different websites that offer workshops to go to Cuba (You can add some others on the comments and they will be added to the post).

Havana Workshops and Photo Tours:

Trip Advisor (I Love Cuba Photo Tours ranked number 1) https://www.tripadvisor.com/Attractions-g147270-Activities-c42-t269-Cuba.html

Cuba Through Your Lens (by my friend Alain Lazaro Gutierrez) https://www.alaingutierrezphotography.com/travel-with-me

Jim Cline Photo Tours https://jimclinephototours.com/cuba-photo-tours-workshops/

Colby Brown Photography https://www.colbybrownphotography.com/photography-workshops/cuba-photography-workshop/

Nomad Photo Expedition https://www.nomadphotoexpeditions.com/photo-tours/cuba/

Cuban Photography Tours https://photographingcuba.com/